What’s atomic mass?

Atomic mass is the mass of an atom. However, when you look on the periodic table, you usually don’t see units attached to atomic mass.

Why are atomic masses unitless?

We can’t see atoms. Because we can’t see them, we can’t weigh them on a scale to record their masses in mg or grams. Therefore, to determine their masses, scientists had to compare their masses to the mass of another atom selected as the standard. Because of this, atomic masses are also called relative atomic masses, where relative means one atom compared to another.

Since we can’t weigh an atom to determine its mass, can we weigh a bunch of atoms to determine their mass?

Yes, we can, if and only if the number of atoms in our unknown bunch is the same as the number of atoms in our other bunch called standard.

How do we know that we have the same number of atoms in each bunch?

In 1811, an Italian physicist called Avogadro had suggested that “equal volumes of all gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of molecules.”

If this is true, it immediately follows that the mass of the equal volumes must be in the same ratio as the mass of the individual gas molecules they contain.

How did Avogadro come to this conclusion?

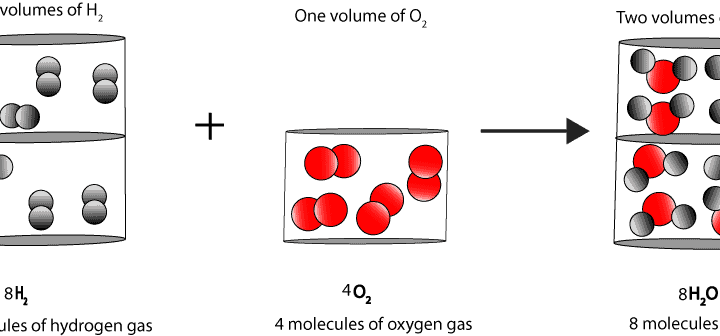

Earlier on one scientist called Gay Lussac had observed that two volumes of hydrogen react with one volume of oxygen to form two volumes of steam (2H2 + O2 –> 2H2O). But Lussac couldn’t explain why the reaction produced two volumes of steam. To explain these results, Avogadro reasoned that if one volume of oxygen contains 100 molecules, then 2 volumes of steam must contain 200 molecules, and for each of these 200 molecules there must be at least one oxygen atom.

How is this possible? How can you get 200 oxygen atoms from 100 oxygen molecules?

Avogadro had an answer. He reasoned that each molecule of oxygen must contain at least two atoms of oxygen. As a result, two atoms of hydrogen must react with one atom of oxygen to form one molecule of water. Here is a model to illustrate his thinking:

How do we know Avogadro was correct in his thinking? As it currently stands, his explanation is consistent with the experimental results.

How can we apply Avogadro’s reasoning to determine the mass of bunch atoms?

Easy! We just have to pick an atom of any element and assign it any value we want. We will then compare every other atom to our standard to determine how light or heavy it is when compared to our standard. From this comparison, we can then construct a table containing the relative atomic masses of all the elements.

If carbon is the standard, what will be the mass of chlorine gas?

If we choose an atom of carbon as our standard and assign it a value of 12, and then in an experiment we find that an atom of chlorine weighs 2.95 times as much as an atom of carbon-12. Then it follows that the atomic mass of chlorine is 2.95 x 12 = 35.45. And the molecular mass of chlorine gas is 2 x 35.45 = 70.9. So, as you can tell, as long as Avogadro’s hypothesis is true, we can choose an atom of any element to be our standard. So clearly, the atomic masses on the periodic table have no units attached to them because they are not actual masses, but relative atomic masses.

To learn how to calculate atomic mass using values from mass spectrometry, click here.